Pinterest seems quite sure that momentary flickers of interest define me.

I never have time for this, but sometimes when I think I do — standing in line at the store or whatever — I’ll open the Pinterest app on my phone and see what it’s offering me now.

Pinterest is a contender for most useless social medium ever. It’s neck-and-neck with LinkedIn, only more fun.

I remember, years and years ago, when I first signed up for it, spending an hour or so scanning through the images being offered, telling myself I needed to do that in order to make the app “work.” I was letting it build a portrait of me and my interests, based on which images I “pinned,” or simply called up to look at better.

I found it an interesting, idle spectacle. Like watching spots of sunlight filter through the leaves of trees in a light breeze. Or watching whitecaps dance on the sea. Or maybe flames in a fireplace.

Actually, the flames make the best comparison, because you can change the patterns somewhat by poking at the logs. And that’s how Pinterest works.

If there’s a practical use for Pinterest, it escapes me. But I suppose it’s mostly harmless, although the mechanism I see in operation is the same as what has made other social media, and sites such as YouTube, such a threat to our reason and our society. As I’ve written here and here and here.

The algorithm is doing that same thing: Asking me to tell it — by “pinning,” or simply by spending time looking — what interests me. And then it says, “If you like that, you’ll love this.” And shows me more and more of the same thing.

Which can be sort of comical, because it leaps to such odd conclusions. Remember that post I wrote about posters I had on my bedroom walls as a kid? Probably not, since it only got two comments, one of them written by me. But I enjoyed writing it — actually, what I enjoyed more was searching the web for the actual images. And the one I played the biggest was the one of Steve McQueen riding a motorcycle on the set of “The Great Escape.” Which may have been my favorite poster. I know that that was my favorite movie when I was a kid.

Anyway, in searching for it, I must have looked on Pinterest. Anyway, it caused the algorithm to assume that I am obsessed with Steve McQueen, especially when he’s riding a motorcycle. I inadvertently reinforced the McQueen thing by pinning a pic or two from “Wanted: Dead or Alive,” which was a favorite show of mine when it was on, 1958-61.

Ever since then, any time I call up the Pinterest homepage, I’ll see five or 10 or more pics of McQueen in a minute of scrolling, often on a bike. They may go away if the app is momentarily distracted by some other assumed “obsession,” but they always come back eventually.

Hey, I like Steve McQueen. Just not that much.

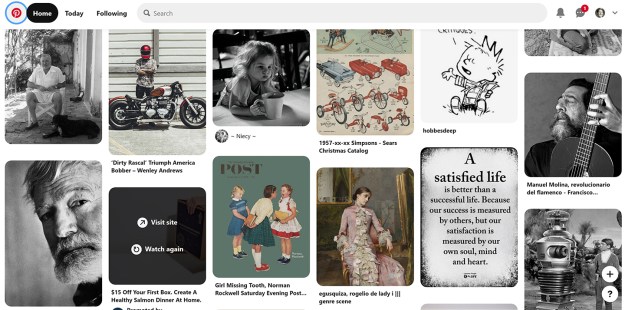

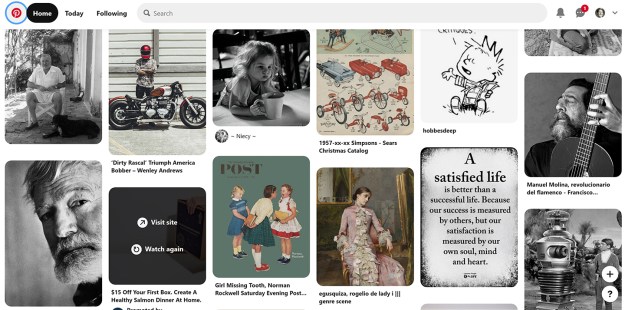

Actually, though, I’m not seeing him much today. Today, the app thinks I’m crazy about flamenco dancers. That’s because lately I’ve been putting random black-and-white pictures on a wide variety of subjects into my “Images” folder. And taking a quick look at the app this morning, I saw this shot with a little girl in the background framing by a wide skirt being flourished by a dancer. I didn’t even notice what kind of dancer it was; I just liked the composition and sense of motion, and thought my daughter the dance teacher might like it.

So now it just knows I’m nuts about flamenco, and I’m getting flamenco dancers left, right and center — especially if they happen to have on polka-dot dresses. It even thinks I want to see a flamenco guitarist, and close-ups of castanets.

Steve McQueen is gone, for the moment.

I’m also getting a lot of pictures of Ernest Hemingway from his late, white-beard phase. This happened because one of my kids really liked cats, so I had pinned a shot of Hemingway with one of his famous Key West cats. Now he’s all over the place, with or without cats, because of that one picture. A little while ago it showed me one of him with a dog (see image below).

It’s fun to mess with the algorithms head like this, if you assume for a moment that it has a head. It takes practically nothing, the smallest gesture on my part, for it to make huge assumptions about what motivates and animates me. And it’s all so wonderfully superficial, because it’s just pictures — the content is so shallow! There’s virtually no text, and what little there is seems to play little role in the process.

The machine isn’t completely stupid. It’s right, for instance, to believe I like Calvin and Hobbes, and Norman Rockwell. And it has an inkling that it can always grab my attention with the kinds of pinup pictures that adorned the noses of warplanes in WWII. But that’s hardly a personality profile.

I’ve been fretting recently about what artificial intelligence is doing to our politics. But I find a few minutes with Pinterest reassuring. Look where it’s going now!, I tell myself. And for that moment, I’m less concerned about AI’s ability to take over the world. Yet, anyway…

EDITOR’S NOTE: Yeah, I know I wrote about this before, years ago. But thinking recently about what these algorithms were doing to our minds, I started playing with this medium again — just to watch the way it works — so I wrote about it again.

The richest man in the world didn’t used to look like this. For instance, here’s J.P. Morgan, at right. He was Mr. Moneybags in his day, and he wielded political power of the sort that I suppose Elon Musk is hoping to obtain by this ridiculous display of his joy at the possibility of electing the most dangerous man in the world. Even Teddy Roosevelt had to consider Morgan in making major policy considerations. He was a force, rather than a mere goofy distraction.

The richest man in the world didn’t used to look like this. For instance, here’s J.P. Morgan, at right. He was Mr. Moneybags in his day, and he wielded political power of the sort that I suppose Elon Musk is hoping to obtain by this ridiculous display of his joy at the possibility of electing the most dangerous man in the world. Even Teddy Roosevelt had to consider Morgan in making major policy considerations. He was a force, rather than a mere goofy distraction.